Director of programming at The Bentway, Altman recently worked on Daan Roosegaarde’s Waterlicht installation (Oct. 12-14) which PIA helped fund.

Altman pictured at the Waterlicht exhibit

What was the most interesting aspect of the planning for the site-wide light installation by Dutch artist Daan Roosegaarde?

Waterlicht is an ephemeral landscape created through the use of LEDs, special software, and lenses. The piece simulates a virtual flood across The Bentway site next to Fort York. Because of this unique character it demands darkness as well as significant community collaboration. We are situated in a dense residential zone, so negotiating the lighting parameters with our neighbours proved to be an interesting challenge, but equally, a great way to build interest in and enthusiasm for the work. The whole neighbourhood is invested in the installation’s success!

From the beginning, it was important to me that this international project was locally responsive and had a lasting impact, extending well

Roosegaarde’s public art intervention simulated a flood in Toronto. The Bentway also organized discussions around climate change. Photo by Nicola Betts

beyond the three-day installation. For this reason, we built partnerships and developed complimentary programming with a number of Toronto-based institutions and organizations including, OCAD, the Ontario Climate Consortium, the Ryerson Urban Water Centre and School of Communications, the AGO, the Great Lakes Waterworks, Waterlution, Swim, Drink Fish and the Rivers Rising project.

Each of these partners took interest in different aspects of the project – its environmental call to action; its acknowledgment of our city’s history; its ephemeral approach to creating public art, etc. It has been amazing to see how a project located at The Bentway has been able to catalyze a city-wide conversation!

The exhibition If, But, What if? (Sept. 14 – Nov. 30) consists of seven site-specific projects. What’s the most challenging part of mounting work with multiple artists?

Mounting any show with multiple artists and ensuring that all the projects receive the attention they deserve is always a challenge. However, If, But, What If? was particularly complicated because we developed the exhibition while the site was still under construction and our understanding of the space changed as the planning unfolded. We had to do a lot of real-time experimentation! Luckily all the artists we worked with were up for the challenge and excited to explore the site along with us.

I’ve learned so much working with this amazing group of artists – Michael Awad, Steven Beckly, Wally Dion, Mani Mazinani and Sanaz Mazinani, Alex McLeod, Sans façon and Jon Sasaki. Each of the artists took the exhibition theme to heart and used their own distinctive practices to explore critical historical moments that changed Toronto’s trajectory and radical acts that will help to shape the future of the city. Through digital mural, sound, sculpture, and photography they grappled with these questions and uncovered opportunities that I never would have imagined were possible.

Before The Bentway you worked for design firms in Toronto and New York. How has your architectural background influenced your current work ?

For me, practicing architecture was never just about designing buildings, but rather, examining ideas and relationships spatially. For that reason, I see my work at The Bentway as a direct extension of my previous practice. The public art and performance-based projects The Bentway is developing and supporting with our partners explore the way we inhabit and engage with the city, the way we create collective spaces, the way we actively interpret our environments. These are all spatial questions.

What is it about working in the realm of public art that challenges you?

Every project is a unique adventure. In fact, I have yet to feel that I have done the same thing twice! To date, I’ve had the good fortune of working with amazing artists, designers, choreographers as well as other curators – so it always remains interesting. The biggest challenge is ensuring that throughout all the logistical and financial planning the integrity of the project and the artists’ vision is never sacrificed. The process always involves creative planning and open lines of communication, but that is what makes it interesting!

What was your first successful creative act?

I had big ambitions at a young age of making it on Star Search! My friends and I spent hours choreographing dances in the basement. We never made it on the show, but to my memory, we did stage some pretty impressive performances for our incredibly patient parents.

How do you begin your day and what are your habits?

I have two wonderful, high-energy and inquisitive five-year old boys who wake me up at the crack of dawn! I have a full day before I even arrive at the office.

Which artists do you admire most?

Some of the artists who I really admire and have been wanting to work with for a long time include, Tauba Auerbach, Tomas Saraceno, Pedro Reyes, Pipilotti Rist and William Forsythe.

Which artists do you like, that would surprise people?

It may surprise people to learn that I really like Douglas Coupland’s public art work. His pieces have a playful spirit that is often absent in the field of public art. Despite the fact that his public pieces tend to be permanent, his work has opened up questions about monumentality and the role public art can and should play in catalyzing and challenging civic memory.

What has been your top art experience?

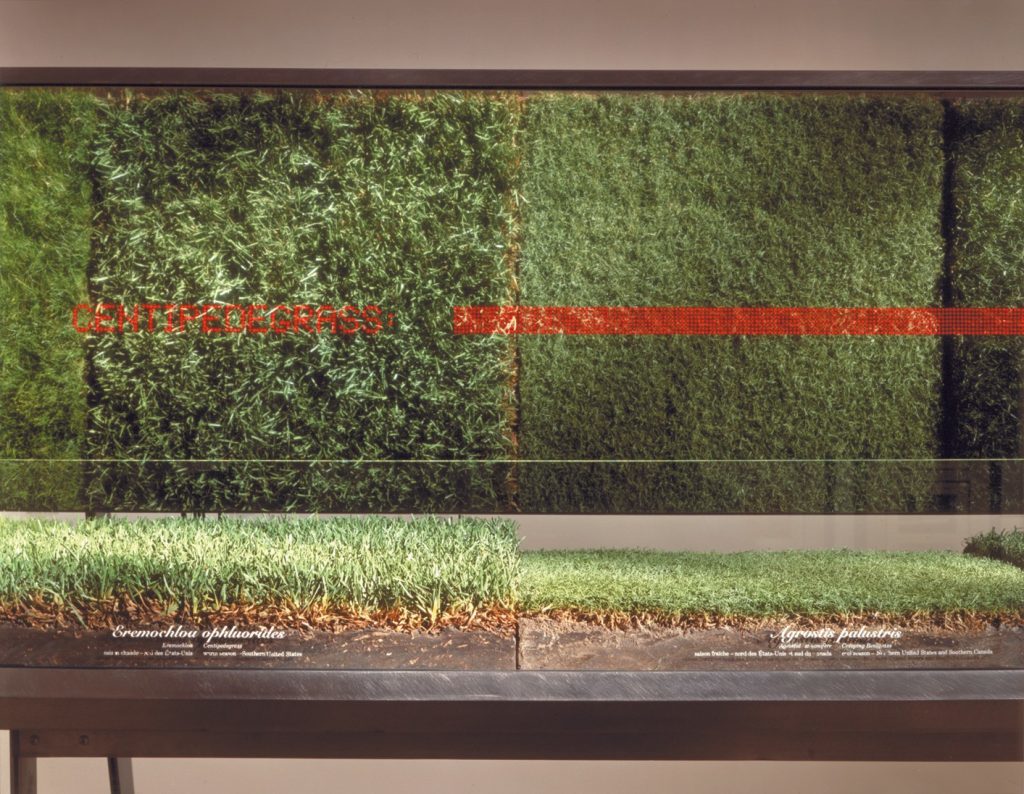

The single show that has had the most significant and lasting impact on my career was The American Lawn: Surface of Everyday Life, created and designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro and presented at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in 1998. It was a forensic exploration of a fam

Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s The American Lawn: Surface of Everyday Life was a huge influence for Altman in 1998.

iliar structure that explored the cultural, political and economic significant of grass. It was beautifully staged and thoughtfully curated. It not only opened my mind to the topic at hand but in addition, to the function and structure of an exhibition. It was when I first understood that an exhibition could be explored as an architectural space. I saw the show shortly after I had started university and it led me to entirely shift my academic focus and pursue a degree in architecture.

Which is more important, the process or result?

They are both equally important. Too often we separate the process and the result, but I prefer to think of all stages of a project as part of a larger continuum. We recently worked on a piece with Wally Dion titled 8-Bit Wampum. It is currently up at The Bentway in front of the Fort York Visitor Centre as part of our fall exhibition. Wally documented his entire working process in video and sent us the clips to communicate his progress and his outstanding questions. It was a remarkable way to correspond with an artist and offered us a window into his personal process that opened up new ways of understanding and interpreting his work.

What is your favourite colour?

It changes, but currently I’m obsessed with amber – the colour of warm light.

How do you procrastinate?

I walk a lot. It helps me clear my head. Sometimes its easier to compose curatorial statements in mind on my walk home than when I’m in the office.

What is your favourite work of art?

James Turrell’s Skyspace Meeting and The Clock by Christian Marclayare both pieces I have spent days with and would happily do so again.

Who would you want to create your portrait?

I’ve fantasized about finding myself in one of Thomas Struth’s Museum Photographs.

What do you do if you need inspiration?

For Altman inspiration can be found here at Type Books of Queen St. W. in Toronto.

I go to Type Books on Queen Street and browse their art and design sections. I go back to the same publications time and time again, but find different interest in the books depending on my current preoccupation.

What do you like to do when not working?

I’m busy being a mom. One of my sons recently told me that The Bentway was his favorite place in Toronto, so work and home clearly have a funny way of blending together. My other son weighed in to make sure I knew his favorite place in the city is still LEGOLAND.

What do you consider your greatest achievement?

Surviving graduate school was my greatest achievement. I’ve never pushed myself so hard academically or creatively. I still find it amazing how often I come back to the ideas I pursued during my thesis, which was centered on the architecture of democracy. I think it is a series of questions I will continue to ask myself over the full course of my career, and explore through a wide variety of mediums.

What is your greatest fear?

I have a deep-seated fear of birds. Sharp beaks and flapping wings really throw me.

What advice do you have for those aspiring to work in the realm of public art?

Work to challenge the definition of public art whenever and however you can. Disregard traditional ideas about permanence and site specificity. Consider the city and your site as your partners. Aim to reach new audiences.

How did you hear about Partners in Art?

Marianne McKenna, who I used to work for at KPMB, introduced me to the amazing work that PIA is doing across the city. From there I went on to meet a number of PIA members whose enthusiasm for the arts was contagious and whose dedication to supporting a thriving arts community here in Toronto is incredibly inspiring. I’ve come to know several of the members better over the past year as we’ve continued to work with Daan Roosegaarde.